Outlander

Diana Gabaldon's 'Outlander' heroine, Claire Randall

The premise of Gabaldon’s story is that Claire, a WWII nurse, reunites with her husband, Frank, for a second honeymoon in Scotand, When she goes for a walk and steps through a group of ancient stones, her life changes forever.

Claire is transported to 18th century Scotland, a land facing the historic battle of Culloden.

Outlander

She’s rescued by Scottish Highlander Jamie Fraser, and the rest, as they say, is literary history.

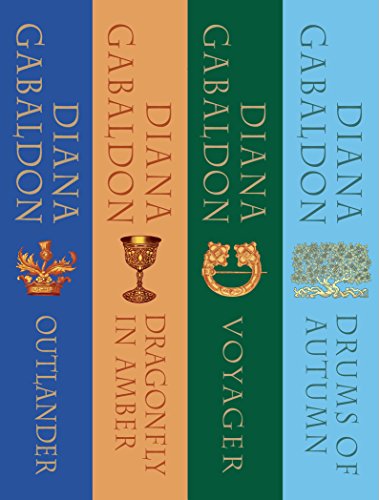

I’ve just finished reading Drums of Autumn. It’s Gabaldon’s fourth book in her Outlander series about the lives, times and romance of Jamie and his time-traveling wife, Claire. They’ve all been best-sellers, and the last book, A Breath of Snow and Ashes, is in bookstores now.

Not only is Claire Randall a striking adventuress, but author Diana Gabaldon herself is a woman who ventures beyond what is considered “customary” for fiction writers.

She breaks a lot of the writing “rules” budding authors read about and hear at conferences. Here are some that come immediately to mind:

Know Your Genre

What genre? Gabaldon admits her first book, Outlander, didn’t fit neatly into any genre.

The Outlander series has elements of romance, historical fiction, family saga and time-travel. It was marketed as a historical romance since romance was considered the largest target market of readers who might like the book.

Some bookstores place Gabaldon’s Outlander books on the romance shelves, some place them on the fiction shelves.

Outlander

For Your First Novel Stay Under 350 Pages.

Her novels in this series far exceed the 300-350 page average, and she does it consistently. With six historical sagas averaging 1,000 pages each, and say 250 words per printed page—that’s a total of about 1,500,000 words!

How does she get away with that?

I consider all reading a learning experience. Here’s what I’ve learned from reading the Outlander series:

First, writers should do like Gabaldon—create memorable characters, like our heroine, Claire Frasier, and her daughter, Brianna.

I’ve heard there are women absolutely obsessed with Jamie Fraser, even though we all know he’s a fictional character.

Gabaldon says, “Good novels are about people.”

From e-mails she’s received she’s come to the conclusion that readers care about Claire and Jamie and their families and want to know all about them, just as we want to hear the latest news about our own family and friends.

Outlander

Conflict and suspense count.

Gabaldon puts her characters in almost constant conflict, not only with each other but with the elements, their environment, and themselves.

She also inserts a regular element of suspense, so that you always wonder, what will happen next? The question can be as great as, how will they survive the forthcoming battle of Cullodon?

Or as simple as, will Roger follow Bree through the stone circle into the past?

There seems to be a question on every page, and you come to anticipate the unexpected. That’s part of the reading adventure.

Gabaldon’s story is all spiced up with details of life and cultures of the eighteenth century that remind me of the Pulitzer-prize-winning historian Barbara Tuchman.

(If you like history and you’ve never read Tuchman, you’re in for a treat; she presents history in a similar fashion.)

In addition to the details of daily life, Gabaldon’s readers learn details of botanical medicine and medical treatments common to the 18th century. All woven into the story-telling in such a natural way as part of personality, conflict and suspense.

Gabaldon’s themes of love are constant throughout the series - Claire’s love of two husbands, mother/daughter love, new young love between Bree and Roger, daughter/father love - Bree’s determination to meet her biological father - and the parts love plays in the lives of several subsidiary characters as well.

There are lots of short scenes, sometimes no more than one page, and always moving the story forward in a compelling manner.

Gabaldon describes herself as simply a story-teller. She doesn’t use an outline, merely writes little excerpts and later puts them all together in some kind of story-telling order that results in the book.

Diana Gabaldon never gave up. “I made only two rules for myself,” she says. “One, I would not give up, no matter how bad I thought it was, until I had finished the complete book, and two, I would do my level best in the writing, at all times.”

She started writing Outlander while she still had a full-time university research position, a part-time writing job and three children under the age of ten.

Gabaldon didn’t write a lot of query letters. She networked online with a reading/writing group, then researched agents based on the encouragement of her online group. Another writer in the group offered to introduce her to his agent.

The agent took her on based on a few of her writing excerpts and a rough synopsis. When she finished the manuscript for Outlander, six months later, he got her a three-book contract.

Pretty good for a lady who says, “I wasn’t trying to be published; I wasn’t even going to show it to anyone. I just wanted to write a book, any kind of book.”

—Carolyn V. Hamilton