Nomad Family

Cam visits a Berber nomad family in Southeastern Morocco

The Berbers are an ancient nomadic people, indigenous inhabitants of North Africa. Their extensive territory ranges across the Sahara from Egypt to Morocco and south to Chad, Niger, Mali and Mauritania, an area larger than the United States.

The friendly family greeted us while seated in a voluminous brown tent woven from goats’ wool. Covering the dirt floor were brightly striped rugs of camel wool.

Nomad Family

The flaps were open to the east to avoid the afternoon sun and westerly breeze which precipitated small, vertical spirals of sand.

The interior was spotless, affected by a twig broom tied with a red cord that stood in a corner. Housekeeping would be a challenge here.

The terrain was desolate: a barren flat expanse of sand scattered with a monochromatic assortment of rocks, boulders, scrub brush, rolling tumbleweeds, and goats – lots of goats. Except for the colorful clothing of the women and children, everything within sight was beige or brown.

Nomad Family

The nomad family unit included parents Zahir and Samira, six daughters ranging in age from four years to young adults and two sons about 8 and 10. The family had other children, older boys who could be seen herding goats along the horizon.

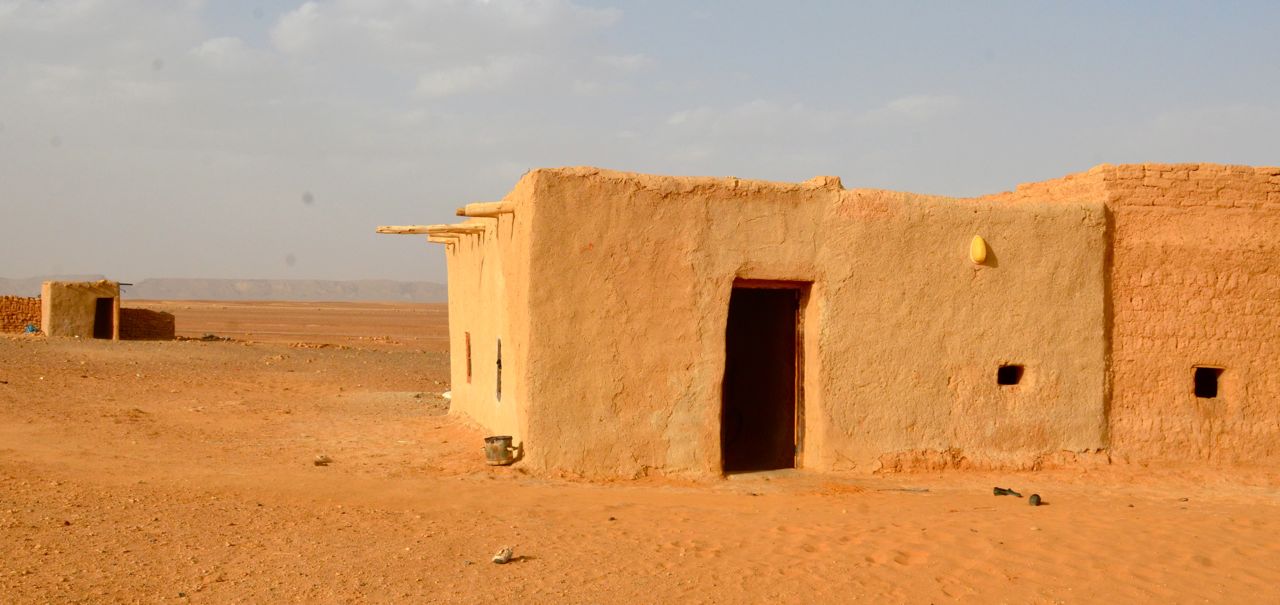

In addition to the tent, there were three small structures. The largest was a two-room building of brown mud where the family slept.

There was no furniture because everyone sleeps on the floor. Blankets and clothing were strewn throughout. Individual shoes were scattered outside as though a hurried round-up did not collect all the pairs.

A corral with one donkey was attached to a small mud shanty which served as shelter for the teenage sons and their dogs which guard the flock from jackals.

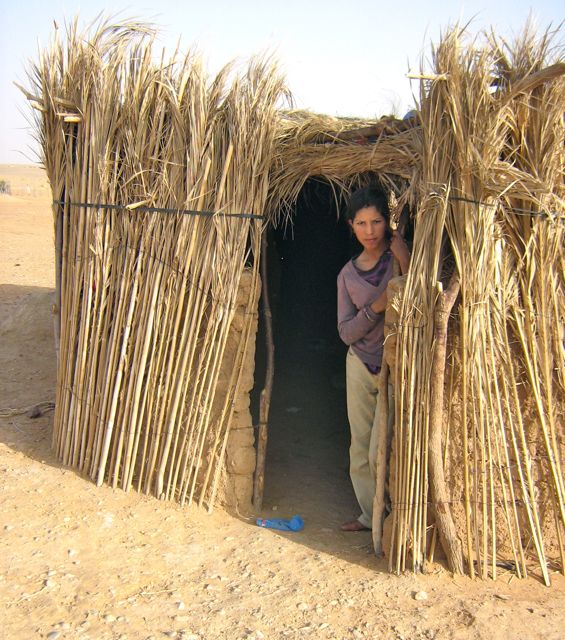

The circular kitchen was surrounded by upright palm fronds leaning against the exterior wall.

Inside, a black cauldron hung over a fire alongside a narrow below-ground pit lined with wood, used for baking bread and roasting meats. Stacks of plastic dishes and bowls lined the wall. Dining is done in the tent or alfresco.

Our excellent guide Larbi El Naijar served as translator since he spoke the local Amazigh dialect. Two of the teens spoke French so we were able to initiate conversations with them.

Nomad Family

Customary mint tea was offered in small glasses and poured from a stylish silver samovar which seemed out of place in the austere setting. We were invited to sit with the family while Larbi handled the lively Q & A session.

The harsh environs in which they survive invited many questions about the culture. There were no electronics products or electricity onsite.

Zahir, below, was fascinated by a camera which displayed the images just taken.

The older women wore

black headscarves, layers of long-sleeved tops with floor-length skirts or

loose trousers. Charcoal outlined their eyes and brows. Two teenage girls were

dressed in slacks.

Samira told us she was married at 18 when her husband was 24. He brought several goats to the marriage and her dowry purchased more livestock. Usually the groom’s family chooses the bride and the couple are introduced at a tribal event before their marriage.

Berbers are nominally

Islamic but are secular and pragmatic rather than devout. The role of women is

strictly defined in this patriarchal society.

As the men tend to the herd, the women remain at the campsite managing the children while cleaning, cooking, and gathering wood and dung for fires. The search for water is continuous with few wells in the parched climate.

The main meal is midday and typically includes tagine (stew), bread, tea, and the ubiquitous dates. When the shepherds are far from the campsites, provisions include dried fruit and meat, cheese made from goat’s milk, and bread wrapped in cloth. The diet seldom varies.

Weekly farmer’s markets offer seasonal foods and also afford the opportunity to socialize away from isolated homesteads. The family earns money by selling yogurt, tanned hides, goats or goats’ meat and the income is used for staples: sugar, tea, barley or sorghum, and clothing.

Occasionally the women create and sell jewelry embedded with stones found during their treks.

With the region’s drought-prone climate, the family moves often in the continuous quest for water and forage. A rented pick-up moves their limited belongings. The women do all the packing, loading and heavy lifting, and walk to the new site with the donkey alongside the truck.

The livestock follow the cycle of seasonal grazing and travel from the desert to the lush summer valleys of the Atlas Mountains, so the entire family migrates.

The men guide the mature flock and average 20 miles a day. The women and children accompany newly-birthed animals who are unable keep pace with the rest of the herd.

The children attend school sporadically since they are required to help with the livestock and must be mobile when the family relocates.

The Moroccan government has initiated a campaign to universally educate Berber children but nomads resist this, reluctant to abandon their unfettered lifestyle while their children attend school.

In recent decades, many young adult and teen girls seeking education, opportunity and a less regimented and demanding fate have opted to move into towns and live with relatives.

Larbi explained that Zahir’s family was genuinely happy to share their life with us. Samira and Zahir exhibited quiet joy in their facial expressions, a purity of heart in their demeanor, and honesty in their eyes.

This family, like hundreds of others in Morocco on the cusp of modernity, exemplifies traditional mores confronted by the twenty-first century.

- Cam Usher-

Photos by Kim Welsh & Cam Usher