In the Footsteps of Nellie Bly

by Rosemary J Brown

Intrepid

journalist and adventurer Nellie Bly believed that ‘nothing is impossible if

one applies a certain amount of energy in the right direction’. Her own 'energy

in the right direction' sent Bly whirling around the globe faster than anyone

ever had in 1889. She raced through a 'man's world' in 72 days -- alone

and literally with the clothes on her back -- to shatter the fictional record

set by Jules Verne's Phileas Fogg in Around

the World in 80 Days.

"Following Nellie Bly: Her Record-Breaking Race Around the World" by Rosemary J Brown

"Following Nellie Bly: Her Record-Breaking Race Around the World" by Rosemary J Brown Nellie Bly in her legendary travel attire (Courtesy of the Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-59924)

Nellie Bly in her legendary travel attire (Courtesy of the Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-59924)Nellie Bly, 25, became a global celebrity. To this day she remains among the top 10 female adventurers.

It was her idea to challenge Fogg’s fictional record 18 years after Jules Verne wrote his legendary novel. But when she introduced her plan to the business manager at the The New York World, he insisted that only a man could follow in Fogg’s footsteps. A woman would require a chaperone and a load of trunks. Bly told him to assign a male; she would offer her idea to another newspaper and win the race. He knew she would and reluctantly conceded.

Even so, Bly’s story idea to race round the globe lay on the editor's desk for a year. Suddenly on 12 November 1889 she was asked if she could start her journey ‘the day after tomorrow’. “I can start this minute,” Bly said. Less than seventy-two hours later, she was aboard the SS Augusta Victoria on the way from New York to Southampton. Her race had begun.

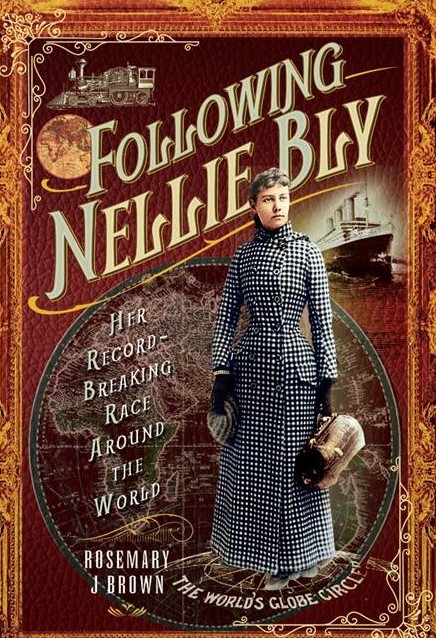

‘Nellie Bly Bids Fogg Good Bye’ trading card (Courtesy of the Alice Marshall Women’s History Collection, Ephemera and Artifacts, Accession No. AKM 91/1.1. Archives and Special Collections at the

Penn State Harrisburg Library, Pennsylvania State University Libraries)

‘Nellie Bly Bids Fogg Good Bye’ trading card (Courtesy of the Alice Marshall Women’s History Collection, Ephemera and Artifacts, Accession No. AKM 91/1.1. Archives and Special Collections at the

Penn State Harrisburg Library, Pennsylvania State University Libraries)A journalist myself with an eye for adventure, I discovered Nellie Bly when I was researching Victorian female travelers online. She jumped off the screen at me. The more I got to know Bly, the more I was enthralled by the courage, determination and daring that sent her circumnavigating the globe solo with a gripsack.

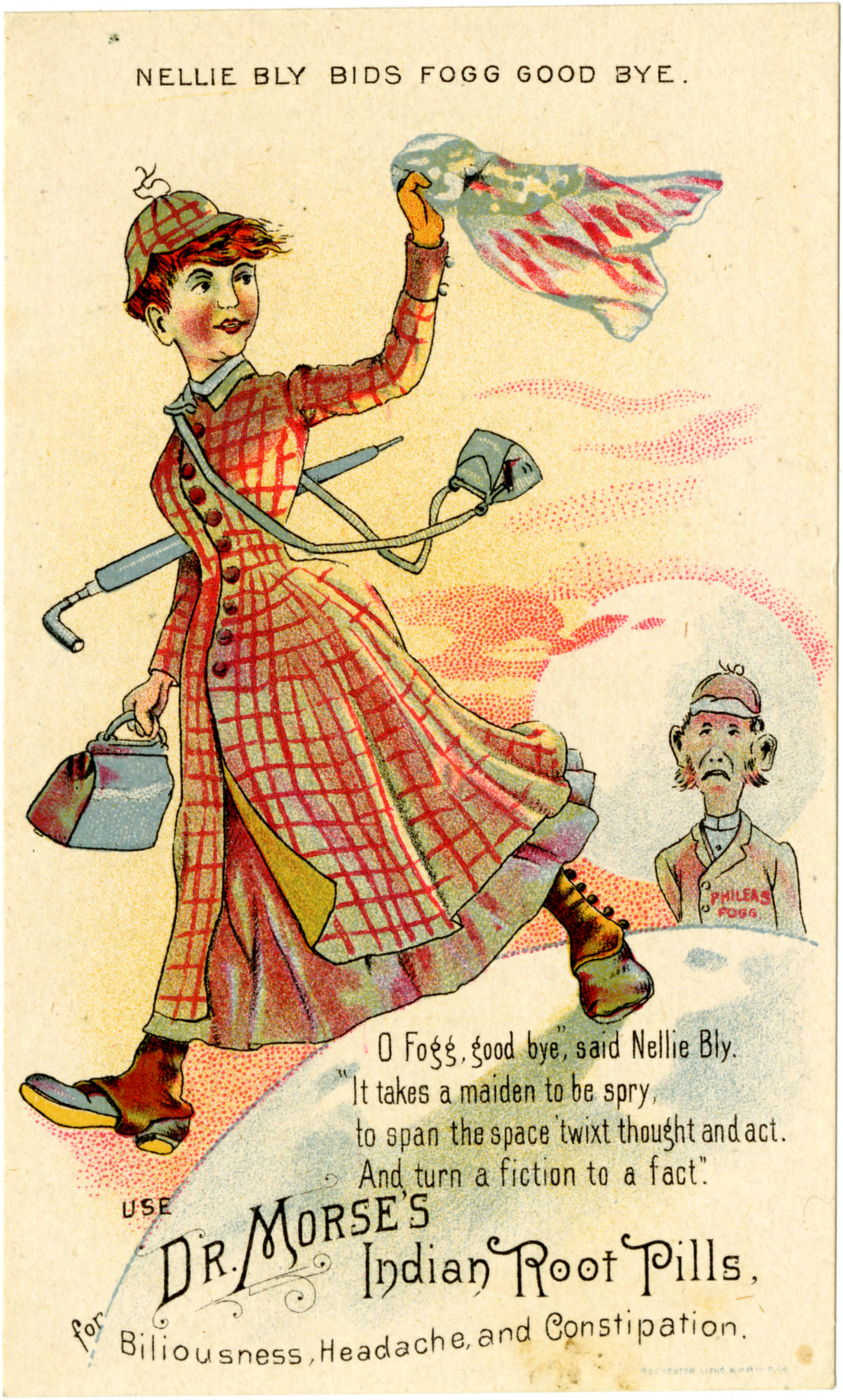

It was that same drive that led her to pioneer a brave new journalism – investigative reporting – when she feigned madness in 1887 to reveal the atrocities inside a women’s insane asylum on Blackwell’s Island (now Roosevelt Island) in New York City. Her exposés led to sweeping reforms across America. Throughout her career, Bly’s reporting gave voices to vulnerable people and challenged oppression wherever she found it.

The New York City insane asylum in Nellie Bly’s day (British Library, accession number: HMNTS 10413.g.22)

The New York City insane asylum in Nellie Bly’s day (British Library, accession number: HMNTS 10413.g.22)That this fearless heroine had faded into oblivion inspired me to revive her, to bring her back as a role model, a reminder that we can achieve the impossible. Although it is her compelling journalism and humanitarianism that I most admire, Nellie Bly was best known for her epic world journey. If I wanted to get her ‘back on the map’ I would need to re-blaze her trail. My goal was to relive her adventure; her book Around the World in 72 Days led the way.

In the Footsteps of Nellie Bly!

My journey began 125 years after hers. Like Bly, I travelled alone with one small bag. The ocean liners that transported Bly have vanished along with many of their routes, so I took to the skies with a round the world ticket. She journeyed through the Victorian era, defying convention en route. I streamed through the digital age.

I followed Bly from the commotion at London's Charing Cross rail station into the calm of Jules Verne's study in Amiens, France, where she interrupted her world race – and risked losing it -- to spend an afternoon with the author who inspired her trip.

Author at Full Moon Poya celebrations in Colombo, Ceylon during her travels

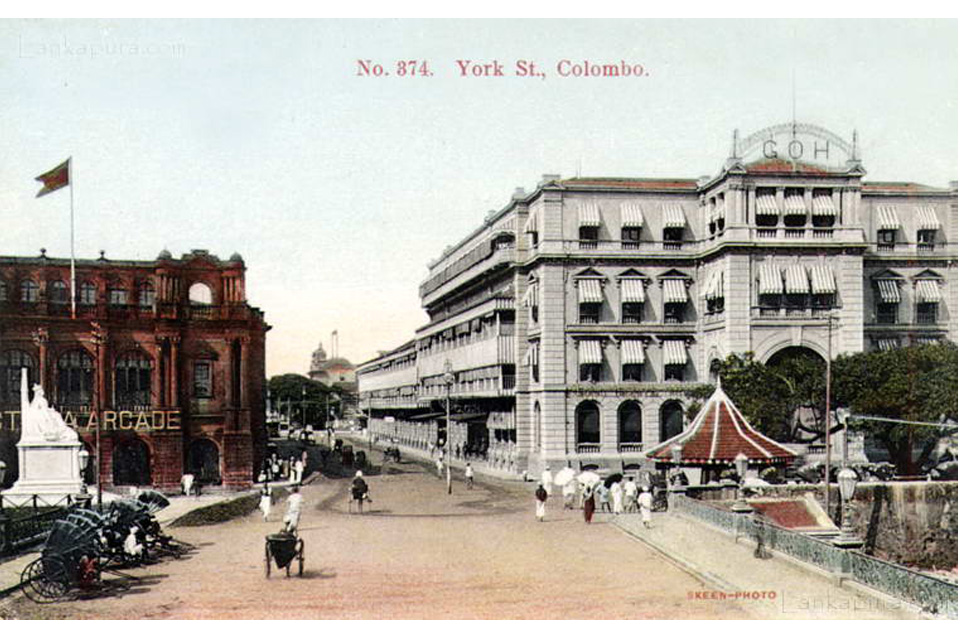

Author at Full Moon Poya celebrations in Colombo, Ceylon during her travels Grand Oriental Hotel, Colombo, Ceylon, circa 1890s (Courtesy of Lankapura, www.lankapura.com)

Grand Oriental Hotel, Colombo, Ceylon, circa 1890s (Courtesy of Lankapura, www.lankapura.com)I lodged at the same hotel -- The Grand Oriental -- in Colombo, Sri Lanka where she spent five anxious nights waiting for the SS Oriental to take her to Singapore. We both sipped tropical juices on the shaded verandas of colonial hotels beside the Indian Ocean, and took the train northeast to Kandy to explore the sacred Temple of the Tooth.

From the jasmine-scented Royal Botanical Gardens in Sri Lanka's hill country to incense-clouded temples in Singapore’s Little India; I tracked the Nellie Bly trail. While she was lavishly entertained in the residence of Singapore’s Governor Sir Cecil Clementi Smith, I was ousted by Ceremonial Guards when I tried to photograph the palladium mansion now home to the country’s first female president.

Hong Kong Harbour in Nellie's time - 1889 (Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program)

Hong Kong Harbour in Nellie's time - 1889 (Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program)Nellie Bly guided me through a raging typhoon – Kalmaegi with winds at 98 miles per hour-- in Hong Kong to gentle autumn showers in Canton (present-day Guangzhou), China where she visited a blood-soaked execution ground and a leper colony. To my great relief, neither can now be traced.

14th century Zhenai Tower, now Guangzhou Museum, Canton, China

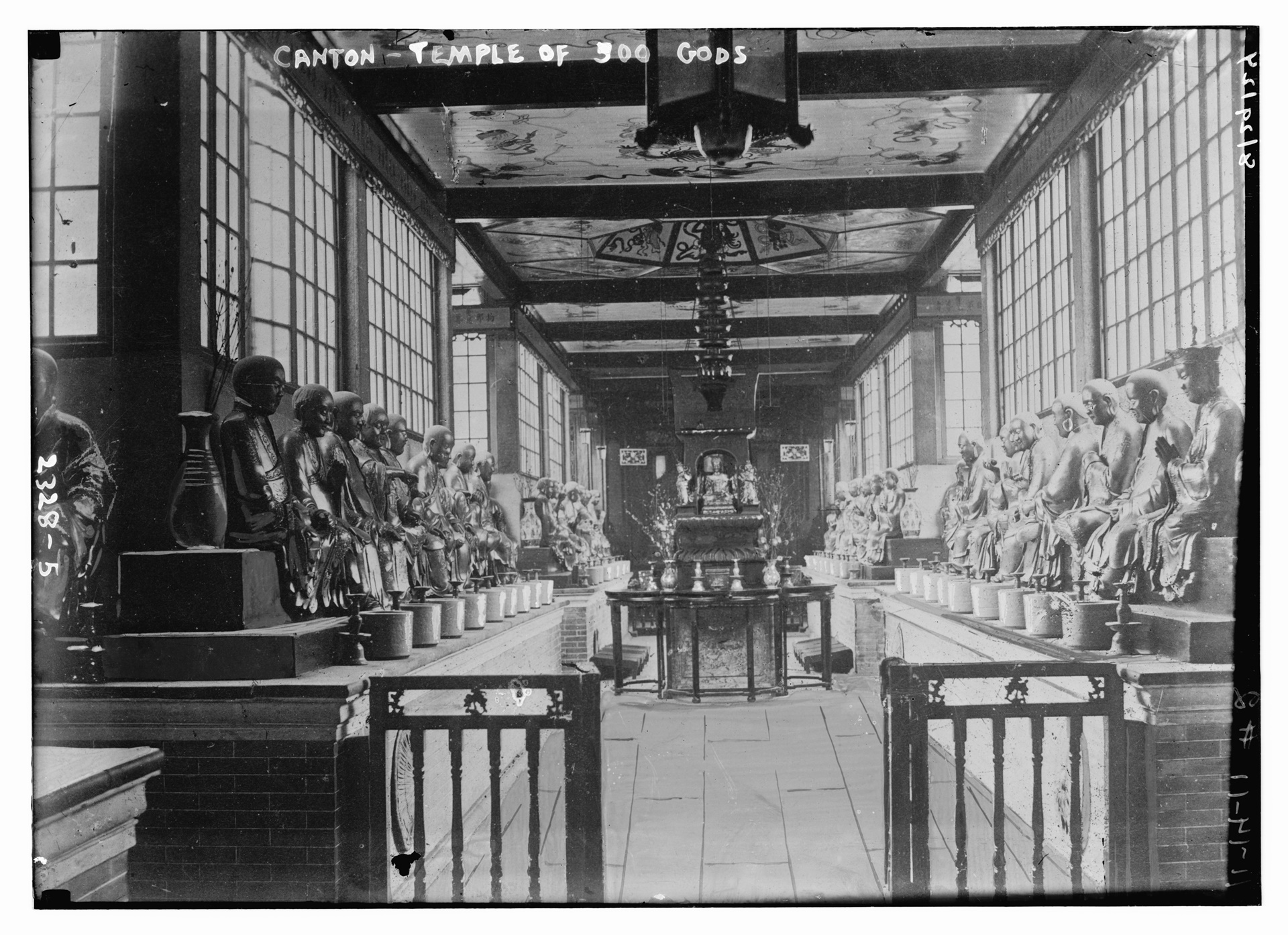

14th century Zhenai Tower, now Guangzhou Museum, Canton, ChinaTemple of the 500 Gods, Canton, China, in Nellie’s time

(Courtesy of the Library of Congress,LC-DIG-ggbain-09935)

(Courtesy of the Library of Congress,LC-DIG-ggbain-09935)Today’s Temple of the 500 Gods, Canton, China, now called Hualin Temple

The usually cynical Nellie Bly fell irretrievably in love with Japan. So did I. Bly climbed a ladder inside Japan's great Kamakura Buddha and gazed through his eyes at the carpeted hills surrounding Mount Fuji. I stepped into his bronze belly 125 years later.

Lap of the Great Buddha, Kamakura, Japan

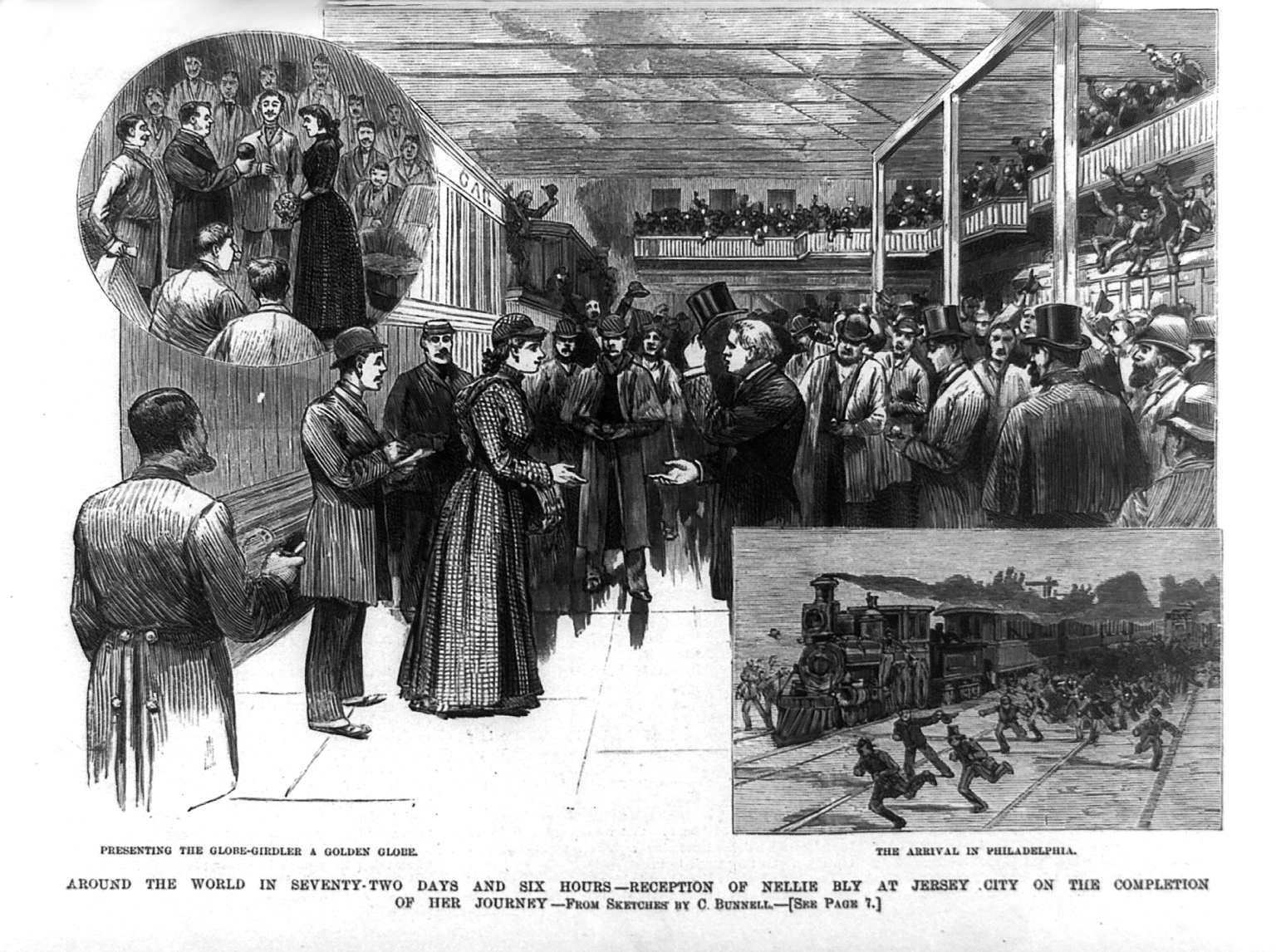

Lap of the Great Buddha, Kamakura, JapanAfter crossing three oceans and four continents, Nellie Bly ended her journey by train across America. I flew from Tokyo to New York to re-trace the start and finish of her iconic voyage. When she arrived home on January 25, 1890, she was said to be the most famous woman in the world. It was ‘the most remarkable of all feats of circumnavigation ever performed by a human being’ The New York World declared.

Nellie Bly’s triumphant arrival and reception in Jersey City after circling the world in seventy-two

days (Courtesy of the Library of Congress LC-USZ61-2126)

Nellie Bly’s triumphant arrival and reception in Jersey City after circling the world in seventy-two

days (Courtesy of the Library of Congress LC-USZ61-2126)Nellie Bly set out to break a record,

dismissing anything that could get in her way – social norms, danger, even the

need for luggage. She wore the same travel ensemble the entire 21,740 miles, avoiding

clothing that shrunk women’s horizons ... and their waists.

She's Broken Every Record!

Front page of The New York World, 26 January 1890

Front page of The New York World, 26 January 1890Traveling on her own across oceans and over continents, she overcame severe sea sickness, freak weather and excruciating delays to circumnavigate the globe in record-breaking time. Impossible was a word that she abhorred. It held no place in her vocabulary and certainly not in her approach to life. With that she triumphed over time, adversity and Victorian propriety to become one of history's greatest female adventurers.

Rosemary laying roses at Nellie Bly’s headstone, Woodlawn Cemetery, New York City (Photo by Alice

Robbins-Fox)

Rosemary laying roses at Nellie Bly’s headstone, Woodlawn Cemetery, New York City (Photo by Alice

Robbins-Fox)Story and Photos by Rosemary J Brown unless otherwise credited.

Read the author's full epic global journey!

"Following Nellie Bly: Her Record-Breaking Race Around the World" by Rosemary J Brown, $34.95 (Casemate IPM) or ask at your local independent bookshop.

Passages from this article first appeared in Third Age Matters magazine.

Author Bio

Rosemary J Brown is a journalist for newspapers and magazines in the UK, USA and France. An avid traveler, she is a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society and a Churchill Fellow. In her quest to put female adventurers 'back on the map' she speaks at the Globetrotters Club, Women of the World festivals and schools, and helped to organize The Heritage of Women in Exploration conference at the Royal Geographical Society.