Pulled into the Fado

"Pulled into the Fado" is a chapter excerpt about Portugal from the travel memoir

'First You Let It Go', by Shiana Seitz. 'Fado' is a style of music in Portugal.

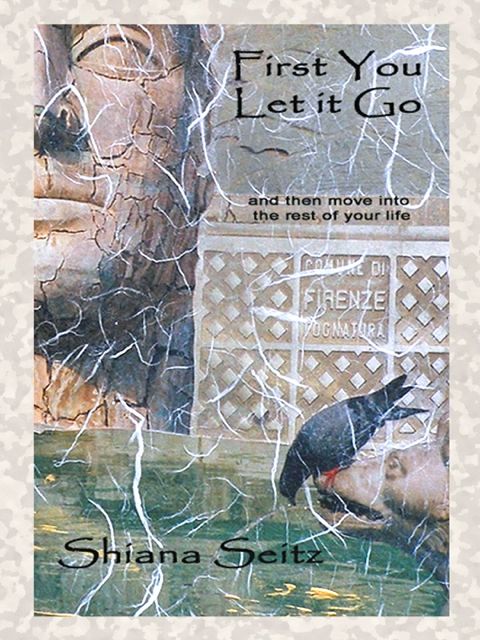

In the southeastern corner of Portugal, I walk with heavy bags on irregular, uneven, even jagged cobblestones from the train station to my hostal. The road to town stretches beside the River Gilão, where multi-colored reflections undulate in the stillness, and crosses a multi-arched Roman bridge that glows like moonstone in the afternoon sun.

In southern Portugal, the waterfront of the ancient town of Tavira.

In southern Portugal, the waterfront of the ancient town of Tavira.To save its cultural heritage, the sleepy village of Tavira has been rebuilding itself for centuries, since the time of the great earthquake in 1755. Every street shows signs of work in progress as people refurbish facades and doorways once built with ability, imagination and care.

In present time the tiles are faded and chipped with colors and detail that hint of a more prosperous time, a time of wealth and trade before the tuna changed their patterns of migration.

My morning beverage becomes meia de leite, or coffee with milk, which I drink with a variety of breads, readily available everywhere.

Following the cobbled corridors of medieval times, I walk past simple

homes and whitewashed churches. Evening finds me at the river’s edge,

besides the trawlers that wait for some future high tide to take them

out beyond the estuary for a day at sea.

A tasty plate of Sardinhas Assadas

A tasty plate of Sardinhas AssadasGrilled sardines are a specialty of the area, so I must try them for dinner with a well-chilled glass of vinho verde, a crisp, light wine. In my naiveté, the only sardines I knew before were tiny, skinned and boned, compressed into a can.

These Sardinhas Assadas are five or six inches long, with charred skin, grilled with olive oil and coarse salt. Delicious!

Fado

I travel on and visit a few of the fishing villages along the southern coast of Portugal. Each shares an antiquated charm with buildings in need of repair. But instead of neglect, the mottled paint reveals a genteel blush of rosy hues and withered affluence; the encrusted and embellished iron imparts a weatherworn sheen.

The charm that I see in this glorification of worn-down buildings is the untold history, the pride from long ago and the creativity of another era. For centuries, these buildings have stood as they are—not torn down, but accepted and used—and I recognize the value in that.

Faro is the southernmost city in Continental Portugal. It is located in the Faro Municipality in southern Portugal. The city proper has 50.000 inhabitants.

Faro waterfront

Faro waterfrontIn the old-town area of Faro, I climb a church tower and look out past the cast iron bells to the waterway, where shallow-bottomed boats navigate a system of channels through marshlands and islands. It is a natural ecosystem and a habitat for a variety of animals.

Storks

StorksIn Faro, storks build elaborate nests on or near many of the towers; if another bird intrudes, the guardian chatters loudly.

On

the southwestern-most tip of the continent of Europe, at the edge of

craggy cliffs soaring high above turbulent waves, the Sagres lighthouse

stands, and steadily sends a beacon of light 100 kilometers out to sea.

Hell's Mouth

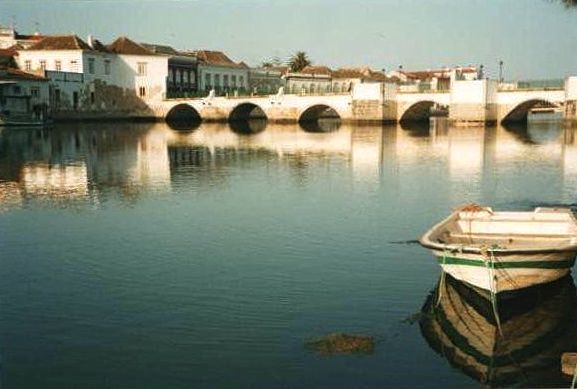

Hell's MouthThis windswept coast was once home to a navigators’ school that readied explorers for adventures in the New World. Windy Cape St. Vincent is actually the most southwestern tip. It has a desolate lighthouse (currently closed for restoration) that marks what was referred to even in prehistoric times as “the end of the world.”

Sagres Lighthouse

Sagres LighthouseI walk precariously on rough and jagged land, while wind whips and braids my hair with salty mists and fills my lungs with the essence of defiance.

At one point in time this area was considered the end of the world, and stories tell about Prince Henry the Navigator, who founded a school of navigation here in the 15th century.

Whether true or not, I cannot even imagine sailing away from a land such as this, in a time when people thought the world was flat. Though perhaps we all do things like that each time we expand our way of life in order to unearth a new experience.

"The church says the earth is flat,

but I know that it is round,

for I have seen the shadow on the moon,

and I have more faith in a shadow than the church."

- Ferdinand Magellen

Fado

Lisbon

By the time I reach Lisbon I am ready to experience the metropolitan area that once was the center of the world’s richest empire.

Lisbon

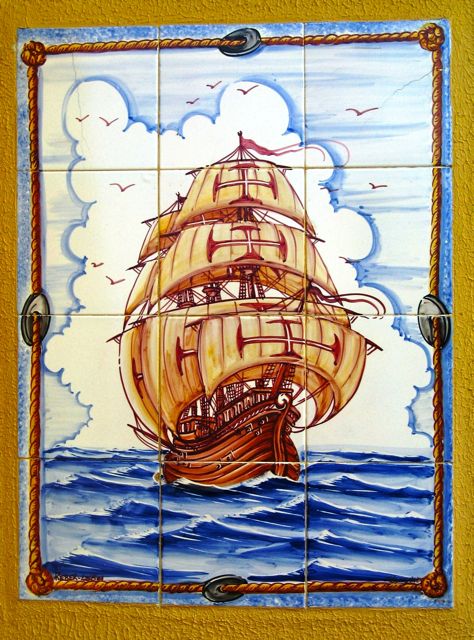

LisbonBlack and white ceramic tiles have paved the pedestrian walkways for

centuries; plazas erupt with fountains and flapping pigeons; the

buildings display picturesque azulejos, hand-painted tile mosaics.

In this city where Portuguese descendants of Africa, Asia, and Europe coexist together I walk the myriad neighborhoods of the Baixa and the Bairro Alto. I ride the ornate century-old exterior elevator de Santa Justa, several floors above the city to get a birds-eye view.

In the morning, I climb the narrow, twisting roads through the Alfama to the only section of the city that survived the great earthquake. This brown, geometric castle stands high upon the hill with a meandering wall, high walkways, boxed-off turrets, and curving arches that stand as the boundary walls between the grounds and the city below.

Back in Lisbon, I sit on a bench on the promenade near my room and rest my weary feet. After while, a fellow traveler crosses my path with a certain look in her eyes. I recognize the sluggishness of her feet as she drags her bag intermittently across the tile walkway and the confusion on her face as she searches for street numbers not easily seen on the walls.

I offer a smile of compassion and understanding, Soon we both discover we’re American and become fast friends for the next few days.

Fado

The next evening with reservations in hand we find the right bus to take us to a restaurant for a dinner show of fado music. They say it’s an expression of the traditional folk music of Portugal. After dinner, the room darkens and the guitarist lures our attention to the stage. As I am with the melancholy of the blues, the twang of country, or the sultry yearnings of the flamenco, I am pulled into the fado with the soulful songs of lost love and broken hearts.

The next day Danielle and I take a day trip to the village of Sintra, the fairy tale-style Moorish village of Portugal.

After

a short train ride, the day grows misty and gray. Castles, palaces and

manor homes rise through the mists with a magical air.

Just before our exploration of the ancient Castelo dos Mouros we meet up with Nicola. Now we are three best friends and climb the steel-gray steps of the castle walls together. The deep steps climb higher and higher, in ways Danielle tells me, of the Great Wall of China, although a thousand years later.

Sintra's famous Queluz Palace

Sintra's famous Queluz PalaceIt is strong and rigid and old, with grand views of the land and village below. We have a delightful day enjoying the sight s and end our adventure at an Italian restaurant with some of Portugal’s excellent green wine.

I feel full and blessed with the abundance of my experiences, but I have only begun to taste the flavors of Europe. Not knowing where to go next, I study my map and decide to return to Spain, as Madrid is a more viable point of departure for additional European travel.

When I learn the only train to Madrid leaves at 10 p.m., I return to my guidebook for an alternate route because it seems to me that if I traveled in a sleeper train I would miss seeing the countryside.

Fado

I chose to go to Aveiro because the guidebook described it as quiet, intriguing, and a popular stop for trains. It is indeed a wholesome little town, divided by canals filled with gondolas, churches, museums and lovely blue azulejos on the walls. The streets are laid with mosaic tiled in black and white.

Black and white Azulejos

Black and white AzulejosAzulejos is a form of Portuguese painted, tin-glazed, ceramic tilework. It has become a typical aspect of Portuguese culture, having been produced without interruption for five centuries. Many azulejos chronicle major historical and cultural aspects of Portuguese history.

My room is delightful, with high, recessed ceilings and bedside lamps.

But the allure of a village criss-crossed with canals and extraordinary

mosaic walkways is not enough to alleviate my transportation problems.

I have witnessed the exhilaration of both Spain and Portugal when their

teams won in futbol. Convertibles and open-windowed cars circle the

streets and plazas with exuberant honking, cheering and bare-chested,

muscular men waving shirts or flags.

But when it is time to book a

ride to Madrid from Aviero, I feel as if i were a human futbol being

thrown and kicked from team to team.

At the train station my first request for a ticket to Madrid is unsuccessful. I go to another counter and am rejected as well. I wait to speak to someone who speaks English and I’m passed from person to person to person; each one makes it clear I cannot go to Madrid or any part of Spain from Aveiro. I am told it is impossible and yet no one suggests an alternative way.

I walk back to the visitor’s center to ask for help. I am told to try the bus station, which is in the other end of town. But the man at the bus station can’t help me either. He gives me a number to call from the phone booth a few blocks away.

On the phone, I wait as I am transferred from one person to another and listen to Portugal’s version of Muzak in between. Eventually, I’m able to communicate in English and learn once again that there is no way to get to Madrid from Aveiro.

Fado

Returning to Lisbon feels emotionally out of the question, so I make the seemingly logical choice to travel north to Porto, the second largest city in Portugal. From there, my guidebook informs me, one can travel by train to Madrid. Surely, a city that size will have a direct route.

I return to the bus station to buy a ticket to Porto, I am directed once again, to confusion. The only bus to Porto is on Saturdays, several days away. The ticket master adds that it would be much better to go by train.

Returning to the train station I’m told the only train to Porto leaves

at 5 a.m., an ungodly hour. There’s too much to do to get to the train

on time; besides, I don’t like the idea of walking to the train at that

time.

Before I leave this scheduling nightmare I stubbornly ask

one more person, this time at the opposite end of the lobby, and I score

a goal!

Not only do I buy a ticket, but I also discover that each end of the train station sells tickets only to their own trains. They’re competitors! Neither company mentions the schedules of the others, nor do they suggest or direct me to the bus office. I additionally learn that trains leave for Porto every hour all day long. I can leave whenever I choose.

After a leisurely morning I leave this “Venice of Portugal” that is rich with canals, bridges and beautiful tiles. With ticket in hand, I now have the time to appreciate the beauty of where I am.

Tile work

Tile workThe railroad station that yesterday caused so much grief consists of white walls stretching up to the balconies, porticos and multiple red-tiled roofs. Blue and white azulejos line the lower floor - both inside and out - with scenes of history, the countryside and village life.

These days the train station is a protected monument and worthy of my notice. How nice it appears today, when viewed in such a different light. As I change my viewpoint, I change my view.

In reality, it takes less time to get to Porto than it did for me to find out how to get here in the first place. As soon as I arrive I buy a ticket to Madrid and quickly learn that the only way to do that is to go south, back through Aveiro to Lisbon, then take the train that leaves from 10 p.m. - the train I originally did not want to take.

Fado

That decision - to avoid the inconvenience of the night train - was the cause of this whole traveling debacle and the new information pushes my buttons all over again. I have absolutely no control over the situation. Whatever sense of balance I had when I arrived is gone. Nonetheless, I buy a ticket for Lisbon to start all over again.

To get to the train tracks I descend a series of stairs, cross the width of several tracks, then climb another set of stairs to wait for the train. In my haste and confusion I end up waiting at the track for chegada, or arrivals, rather than the track for partida, or departure.

Very few people are waiting on the platform, but I don’t realize until too late that I am not where I belong. The train I’m waiting for is now leaving from the other side of the tracks. Down and up a staircase away. Standing alone on the platform, I watch it leave the station as the sun approaches the horizon.

I earnestly tried to make something happen by reading the guidebooks and talking to officials who spoke my language. I took responsibility for my actions but it was beyond my control.

During the whole process I

moved through the myriad tracks of emotions, from anger into frustration

and more anger into compliance, to get where I am - watching the last

train of the day chug away.

The only thing left to do is surrender - to accept the things I cannot change, to change the things I can, and...to let it go.

I

return to the lobby, book a ticket for the next day, find

accommodations, and move on to explore a city filled with hills, history

and gigantic barrels of port.

Shiana Seitz

Shiana Seitz

Shiana Seitz, from her memoir 'First You Let It Go'. Photos by Shiana Seitz and Carolyn V. Hamilton

- Home ›

- True Tales ›

- Fado