Celebrating Thanksgiving Haiti

A different way of celebrating Thanksgiving Haiti style!

When my partner Sara and I moved to Haiti after the 2010 earthquake leveled most of Port-au-Prince, we faced some serious challenges.

Sara directed recovery efforts for a major international housing NGO. I accompanied her in a non-official capacity. When Sara began looking for our home there, I had only one request: I wanted an oven.

Housing in Port-au-Prince

Housing in Port-au-PrinceWe relocated to Port-au-Prince from Vietnam, where we had lived for a year with only a cook top in our kitchen. I hated our oven-less life. I wanted to bake.

So Sara did what any cake-loving partner would do. She found us a home in Haiti that featured an oven - a real, honest-to-goodness gas oven - minus the thermostat.

"Are you serious?" I said, when I realized that there was no way to set any specific temperature on our less-than-perfect-by-American-standards home appliance - any temperature, either Fahrenheit or Celsius.

"Oh, that's not that important. You'll figure it out," Sara insisted.

Kathy with her new gas stove and oven

Kathy with her new gas stove and ovenOver the coming months I moaned to myself when twelve attempts and twelve burnt batches of Schnickerdoodles later, I was still “figuring.”

But for Thanksgiving I needed an oven, a temperature-controlled oven. I whined in my own mind, and sometimes to Sara.

As an American I couldn't imagine celebrating Thanksgiving without pumpkin pie. It’s the Macy's Parade of Thanksgiving desserts—even when celebrating from Port-au-Prince, a far-away, cholera-sickened, earthquake-toppled corner of the Caribbean that was feeling less and less like home.

Now, a pumpkin pie likes to bake for the first 15 minutes at 425 degrees Fahrenheit and the final 45 at 350, temperatures too precise to register on the oven thermometer I'd brought back from the U.S., hoping to resolve this issue.

Celebrating Thanksgiving Haiti

That thermometer only got me in the ballpark of a particular temperature, give or take 100 degrees—not exactly the kind of precision I wanted.

Then, when Sara struggled to duplicate the thermostatic requirements of the Butterball we'd managed to find—not an easy feat—I reminded her, "Oh, that's not that important. You'll figure it out."

Shopping challenges also threatened our Haitian holiday.

Wisely, Sara and I had brought back from the US several Thanksgiving comfort foods we worried wouldn't be available even in the expat-oriented grocery stores in Petion-ville, the upscale Port-au-Prince suburb where we lived.

One of these was canned pumpkin.

As it turned out, it seemed there wasn't an ounce of Libby's to be had on the entire island. Cherry pie filling, yes, canned yams, yes, canned pumpkin in time for Thanksgiving pie-baking, no sir, none of it—anywhere. And believe me, I looked.

I didn't have a thermostatically-controlled oven to bake the pie in, but I did have a full, 29-ounce can of "America's Favorite Pumpkin" to put in it - thanks to my gift for what Sara deems OVER-packing. OVER, my ass! Did she want pumpkin pie or not?

I had another seemingly "serious" scare two days before Thanksgiving when I tried to track down celery.

Celebrating Thanksgiving Haiti

Standing in Giant Market unable to find this vegetable, almost as essential to stuffing as sage itself, I came close to a celery-induced panic attack. I found myself wondering, "What would Jesus do?" What would the son of God himself - assuming he were a turkey-stuffing kind of carpenter - use in his stuffing, were celery not available? If he turned water into wine, could he turn carrots into celery? Could we?

In the end, it was Sara herself who performed a miracle, finding a celery-looking substance in a store near her office. Catastrophe averted. We were that much closer to stuffing the bird we hoped to roast, at a temperature that was not yet determined.

Then, the day before Thanksgiving Sara sent me to the supermarket for chicken broth.

Actually, Giant carried the item in both the Swanson and Campbell's varieties— the Campbell's canned with MSG, the Swanson's, in a carton and without. Being a health-conscious, not-wanting-to-consume-excessive-amounts-of-sodium American, I selected the latter.

In fact, I tried to check out with three cartons of the stuff, since Thanksgiving dinner calls for broth in both the gravy and as a moistening agent in any celery-rich stuffing.

Now there was a new hitch. Though the store had over-stocked the Swanson's, they wouldn't sell it to me. And, if sheer quantity were any indication, wouldn't sell to anybody, for that matter. They couldn't decide on a price.

So, when, after thirty minutes of trying to determine one, no member of the sales or management staff could still settle on an amount to make me pay, I suggested they charge me anything.

"Over-charge me," the comfortable-and-coddled-in-me offered, a concept they seemed not to grasp.

Celebrating Thanksgiving Haiti

Kathy & Sara's Thanksgiving table

Kathy & Sara's Thanksgiving tableUndeterred and unwilling to waste any more of my time-is-money American minutes, I gave up, bought the cans of Campbell's, and headed home, risking ill-health in the coming days.

As it turned out, the MSG didn't matter.

Celery, perhaps the most frivolous of vegetables, didn't make or break our stuffing. The turkey roasted perfectly, even without a thermostat. The pies baked beautifully, or, at least, beautifully enough. Our dinner was delicious.

Still, the lovely meal we ultimately served our 24 expat friends also ate at me.

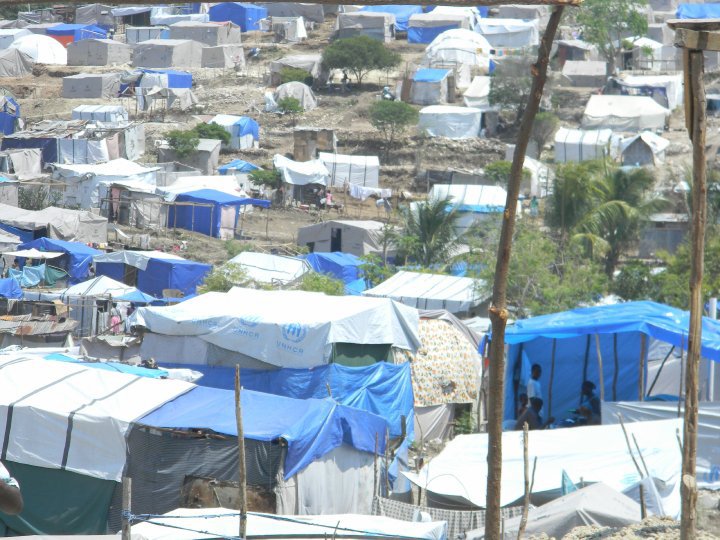

Haitian children in Port-au-Prince

Haitian children in Port-au-PrinceThree years later I continue to ponder the ethical implications of hosting a feast for folks with plent to eat in a country where children remain hungry, where they are sent to bed without a drop of dinner and wake in the morning with no substantial breakfast.

I have yet to resolve this—the fact that famine and feasting both exist in the same world at the same time, sometimes within mere meters of one another.

I don't mean to imply that this Thanksgiving Americans should step away from their own plates. That helps no one. Perhaps it’s important that I step up to the plate in other ways. Could I make more of a difference?

I come from a country with an obesity epidemic but lived in one plagued with not enough food and a population too poor to feed itself. This was a painful irony.

It still is.

I still struggle with guilt about that dinner.

I still ask myself if Black Friday morning in America could mean more breakfast for Haiti.

Kathryn McCullough

Kathryn McCulloughKathryn McCullough is an author, artist, and former academic, who lives in Cuenca, Ecuador. She’s working on a memoir about growing up in an organized crime family and blogs at “Reinventing the Event Horizon.” Kathryn writes periodically for the Huffington Post, where an earlier version of this essay was published in 2012.